Last week we took a cultural field trip, visiting the Columbus Museum of Art to view the Dresden Tapestries, based on cartoons by Raphael in 1515-16 and commissioned by Pope Leo X to hang in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. Although we had seen tapestries in French chateaux and other European museums, this was our first opportunity to get a little closer and to learn more about how they are made. The bottom line: they are really art times two, the artist’s initial cartoon and the fiber art of the tapestry produced from it.

What is a tapestry?

The more intimate setting of the Columbus museum and the quiet weekday timing offered a perfect opportunity to view the tapestries more closely. A docent gave the group we were with a basic overview of tapestry weaving as well as the history of these particular pieces. Tapestries are a unique fabric art, woven to portray a scene, story or event, often biblical or historic. These tapestries focus on the ministries of Saints Peter and Paul. But more about that later.

In essence the tapestry subject is a woven copy of a drawing (known as a cartoon) created by an artist. Tapestries are painstakingly handwoven — most often by European workshops specializing in this art form — with the design on one side of the fabric. To do this, the cartoon is copied (by hand!) and the copy laid face-down on the fabric. The finished tapestry becomes a complete reverse of the original cartoon. The cartoons for the original set of these tapestries were sent to Brussels to be woven in the workshop of Pier van Aelst. They were probably completed in 1520.

About the Raphael tapestries

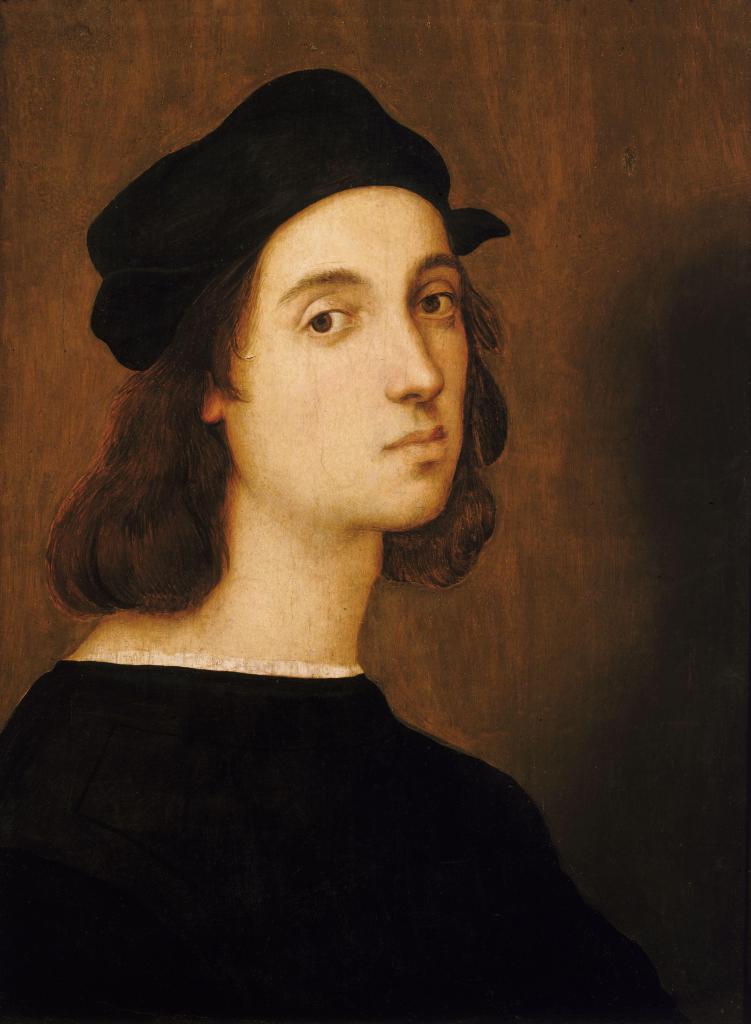

My knowledge of Raphael was pretty sketchy, so after the museum visit I delved a little more into his life and his role in the Renaissance art world (Of course, it would have been even better if I’d done this homework first!). Along with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael is considered one of the three architects of the High Renaissance, a period from as early as 1495 to as late as 1530 of exceptional artistic accomplishment in Rome and Florence, Italy.

Artistic temperaments played a part in Renaissance art. Historians point out that Michelangelo was no fan of Raphael and openly critical of his work. Raphael was generally thought to be more agreeable and charming, traits that may have played a part in his success in acquiring significant commissions. In developing the cartoons for this series of tapestries, Raphael was very aware that they would be in close proximity to Michelangelo’s famous ceiling in the Sistine Chapel; however, the subject matter — Christ turning over the church to Peter and Paul — was different.

Like many artists, Raphael got an early start; his father was a court painter and Raphael was apprenticed at a young age to another master. After time spent elsewhere in Italy, he found his way first to Florence and eventually to Rome. His reputation firmly established, one biographer noted that Raphael had a workshop of fifty pupils and assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own right. This was arguably the largest workshop team under any single master painter. The workshop included masters from other parts of Italy, probably working with their own teams as sub-contractors, as well as pupils and journeymen. There is little evidence of the internal working arrangements of the workshop, but this was the artistic custom of that time. Raphael died quite young (at age 37 in 1520). He is perhaps best known for the frescoed Raphael Rooms in the Sistine Chapel. The series of 10 cartoons for tapestries representing the lives of Saint Peter and Saint Paul was commissioned by Pope Leo X in about 1516.

The Dresden tapestries are one of numerous sets woven from these cartoons after Raphael’s death. Seven of Raphael’s original 10 cartoons for the series have survived and are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The tapestries woven for the Vatican no longer hang in the Sistine Chapel but are displayed on a rotating basis in the Vatican Museum. They returned briefly to the Sistine Chapel in 2020 in honor of the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death.

The impact of the tapestries and Raphael in the art world is evident in the second part of the exhibition, which includes drawings by Raphael that were studies for his cartoons. Numerous other works—paintings, prints, drawings, and sculpture—were created by artists influenced by Raphael’s designs. The artist’s style and in some cases entire images were lifted from the much larger tapestries to become art on their own or to be worked into other pieces. Noted renaissance and baroque masters such as Rubens and Poussin are among the artists who incorporated Raphael’s work into their own.

The Columbus exhibit is comprised of six works from the duplicates ordered by the Prince of Wales (later King Charles I) about 100 years after Raphael’s death. (Here’s where the world history kicks in.) They were produced by tapestry makers in Mortlake, England. Augustus the Strong, elector of Saxony and king of Poland, brought the tapestries to Dresden, Germany in the 18th century. The tapestries were restored in the late 20th and early 21st century. The Columbus exhibition is the first time they have been displayed outside Europe.

Two lessons in one

I think I always looked at tapestries as works of art, but certainly without appreciating the entire process. First, the artist creating the cartoon has to plan the scene, starting with a series of rough sketches that are refined into final drawings to be included in the cartoon. These are huge works with significant detail and background scenery. This is where the other artists in the master’s workshop came into their own, copying the master artist’s style and intent. This is the first art lesson. The artistry of the tapestry weavers is the second lesson. Perhaps time for more research?

I don’t know about you, but I love when a “field trip” of some sort sets me off on subsequent pursuits. I’d like to know more about the lives of Raphael and Michelangelo. Can you imagine these men elbowing their way for favor among the papal and royal interests of their day? I know Francis I lured Leonardo da Vinci to his chateau in Amboise, France, where da Vinci (and the Mona Lisa) remained until his death. What story lines would you pursue?

Thank you so much for stopping by for my impromptu art history class. See you again soon!

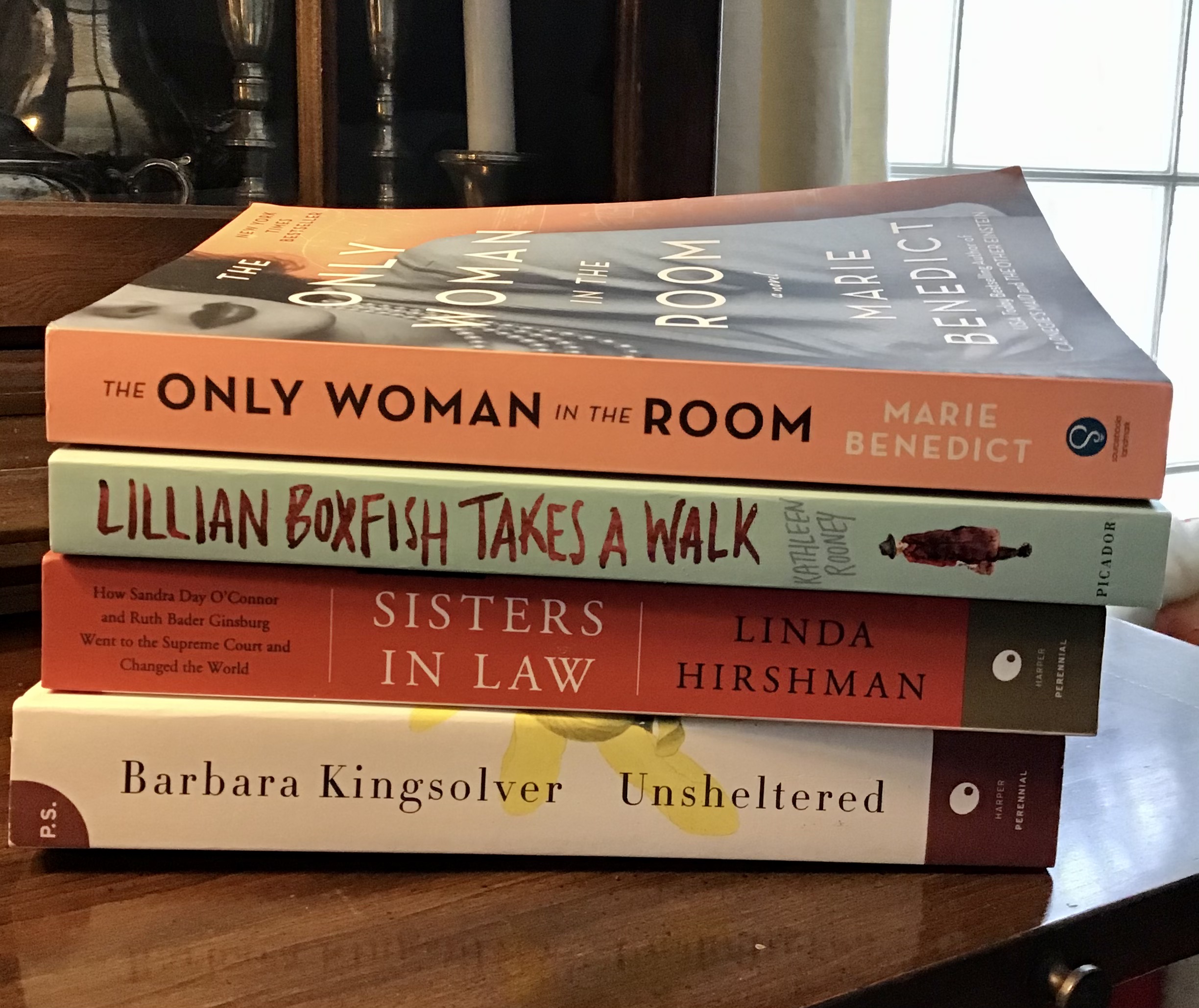

I had planned to talk about the to-be-read and to-be-cooked lists I’ve been compiling for the new year, along with a few stabs I’ve made at de-cluttering and the other ways in which I was planning to entertain myself while we wait out the pandemic. (In the county were I live the Health Department describes the risk of infection as “substantial.” I don’t know what that means but it doesn’t sound good, does it?

I had planned to talk about the to-be-read and to-be-cooked lists I’ve been compiling for the new year, along with a few stabs I’ve made at de-cluttering and the other ways in which I was planning to entertain myself while we wait out the pandemic. (In the county were I live the Health Department describes the risk of infection as “substantial.” I don’t know what that means but it doesn’t sound good, does it?

My grandfather was a WWI veteran and a founding member of the William McKinley American Legion Post in Chicago. When he died in 1988, his friends from the post showed up to honor him as pallbearers. When the minister had finished his blessing at the cemetery and was about to send the mourners to lunch, one of the legion members, a little white-haired man (in his nineties I imagine, as Grandpa had been) with his legion cap at a rakish angle, stepped forwarded and admonished the minister to “Hold on sonny.” Then he produced a tape player, pushed a button, and played Taps. (And we all cried a little more. )

My grandfather was a WWI veteran and a founding member of the William McKinley American Legion Post in Chicago. When he died in 1988, his friends from the post showed up to honor him as pallbearers. When the minister had finished his blessing at the cemetery and was about to send the mourners to lunch, one of the legion members, a little white-haired man (in his nineties I imagine, as Grandpa had been) with his legion cap at a rakish angle, stepped forwarded and admonished the minister to “Hold on sonny.” Then he produced a tape player, pushed a button, and played Taps. (And we all cried a little more. )

Finally, we got to McKinley Park, 69 acres of green in the midst of the city, with a lagoon where my mom and uncle ice skated, a field house, and so many ball fields where Dad and my uncle spent a significant part of their lives. In fact, they met there and played ball, sometimes together and sometimes against each other, long before Mom and Dad met. It’s still a leafy oasis, popular with runners and walkers. On this September Saturday, there were soccer and baseball games. It’s still the magnet it always was.

Finally, we got to McKinley Park, 69 acres of green in the midst of the city, with a lagoon where my mom and uncle ice skated, a field house, and so many ball fields where Dad and my uncle spent a significant part of their lives. In fact, they met there and played ball, sometimes together and sometimes against each other, long before Mom and Dad met. It’s still a leafy oasis, popular with runners and walkers. On this September Saturday, there were soccer and baseball games. It’s still the magnet it always was.

Speaking of grandsons and baseball, Steve and I spent the weekend in Ohio carrying our folding chairs from game to game, following the five-year-old and his T-ball team and the eight-year-old and his coach pitch team (who seem like pro’s after watching T-ball).

Speaking of grandsons and baseball, Steve and I spent the weekend in Ohio carrying our folding chairs from game to game, following the five-year-old and his T-ball team and the eight-year-old and his coach pitch team (who seem like pro’s after watching T-ball).

The next day we were up early and walked the half-block our so from our hotel to the departure point for the various D-Day tour operators. Ours was a small group tour, maybe 12 of us in a van. The guide was a young man from Wales who told us he’d become fascinated by all aspects of WWII as a young boy when his grandfather began taking him to some sights. His knowledge was encyclopedic; clearly he was a very good student.

The next day we were up early and walked the half-block our so from our hotel to the departure point for the various D-Day tour operators. Ours was a small group tour, maybe 12 of us in a van. The guide was a young man from Wales who told us he’d become fascinated by all aspects of WWII as a young boy when his grandfather began taking him to some sights. His knowledge was encyclopedic; clearly he was a very good student.

Utah Beach, Sainte Mere Eglise, & Pointe du Hoc

Utah Beach, Sainte Mere Eglise, & Pointe du Hoc

Pointe du Hoc was the highest point along the coast between the Omaha and Utah landing beaches. In 1943 Germans troops built an extensive battery here using six French WWI artillery guns and early in 1944 began adding to the battery. D-Day plans included an assault by specially trained Army Rangers to breach the steep cliffs and disable the guns. The cliffs are formidable here and the ground atop them is pock-marked by bombings and gun placements. It’s rough to walk today, particularly in a sharp wind, and impossible to imagine how challenging it was on D-Day.

Pointe du Hoc was the highest point along the coast between the Omaha and Utah landing beaches. In 1943 Germans troops built an extensive battery here using six French WWI artillery guns and early in 1944 began adding to the battery. D-Day plans included an assault by specially trained Army Rangers to breach the steep cliffs and disable the guns. The cliffs are formidable here and the ground atop them is pock-marked by bombings and gun placements. It’s rough to walk today, particularly in a sharp wind, and impossible to imagine how challenging it was on D-Day.

Our guide timed our visit to the American Cemetery for the hour when the flag is lowered at the end of the day. Walking to the cemetery I was tired. Despite lovely clear skies and fair weather, it was a very windy day, and we had already walked a lot. But I think I was also feeling emotionally spent. It’s not possible to walk these roads and towns without thinking of the people who came before. And not just the soldiers. But the brave French citizens who loved their communities and way of life, who were totally upended by the German invaders, many of them risking their lives working with the French underground, and who in the end so gratefully welcomed the Allies.

Our guide timed our visit to the American Cemetery for the hour when the flag is lowered at the end of the day. Walking to the cemetery I was tired. Despite lovely clear skies and fair weather, it was a very windy day, and we had already walked a lot. But I think I was also feeling emotionally spent. It’s not possible to walk these roads and towns without thinking of the people who came before. And not just the soldiers. But the brave French citizens who loved their communities and way of life, who were totally upended by the German invaders, many of them risking their lives working with the French underground, and who in the end so gratefully welcomed the Allies. We ended the day at Omaha Beach, and our guide took the time here to diagram, using a stick in the sand, exactly how the landings unfolded and how they fit into the great scheme of the entire D-Day invasion. (Again, he was just so knowledgeable!)

We ended the day at Omaha Beach, and our guide took the time here to diagram, using a stick in the sand, exactly how the landings unfolded and how they fit into the great scheme of the entire D-Day invasion. (Again, he was just so knowledgeable!)